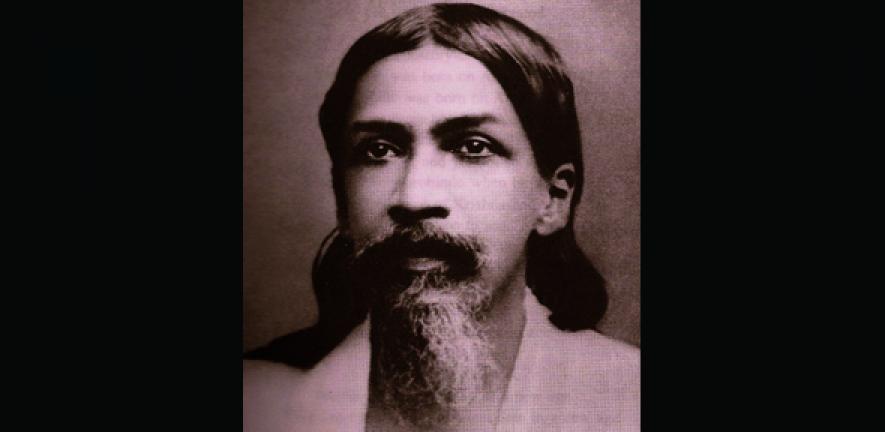

In 1879, a young Indian boy arrived in England from Calcutta (now Kolkata), in the state of Bengal, sent by his father to receive a British education. Aurobindo Ghosh showed enormous promise and would go on to receive a scholarship to study classics at King’s College, Cambridge.

By the time he had moved back to Calcutta in 1906, the state had been split in half by Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India. The British claimed this schism was ‘administrative’, but it was largely an attempt to quell burgeoning political dissent in the region.

The partitioning of Bengal – a prime example of British ‘divide and rule’ policy – incensed many sections of the population, and the Indian ‘middle classes’ mobilised under the banner of Swadeshi, the anti-imperial resistance movement that would eventually force the British to revoke the partition six years later.

While ‘moderate’ Indian leaders lobbied the British for greater representation, many of the younger generation in Bengal – particularly Hindus – believed that ‘prayer, petition and protest’ would fail, and more radical action was needed: non-cooperation, law-breaking and even violence, in the name of ‘Swaraj’ – self-rule. One of the figureheads of ‘extremist’ Swadeshi was Aurobindo, a teacher, poet, polemical journalist and underground revolutionary leader.

In his later years, Aurobindo became one of India’s most influential international Gurus, redefining Hinduism for the modern age with his experimental mysticism (Integral Yoga), global outlook and life-affirming metaphysics of divine evolution. His philosophy is taught across India and was recognised early on by prominent Western figures including Aldous Huxley, who nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1950. He was also a major inspiration for the ‘New Age’ movement that swept across the West.

Today, the popular perception of Aurobindo’s life is divided. The early political firebrand and later mystic are seen as separate identities, split by a year of imprisonment during which Aurobindo was spiritually ‘awakened’.

However, for Alex Wolfers, a researcher at Cambridge’s Faculty of Divinity, this dichotomy is a false one. The spiritual and political blurred throughout Aurobindo’s extraordinary life, particularly during his time as a leading light of radical Swadeshi, says Wolfers, who is investigating spirituality in Aurobindo’s early political writing.

Through research at archives in Delhi, Kolkata and Aurobindo’s Ashram in Pondicherry, Wolfers has traced the emergence of a new theology of revolution in Aurobindo’s thoughts, one that harnessed the spiritual to challenge “the sordid interests of British capital”.

Aurobindo fused the political and spiritual, mixing ideas from European philosophy, particularly Hegel and Nietzsche, with Hindu theology under the aegis of the Tantric mother goddess, Kali, and Bengali Shaktism – the worship of latent creative energy – to develop a radical political discourse of embodied spirituality, heroic sacrifice and transformative violence.

He complemented this with poetic interpretations of the French revolution and Ireland’s growing Celtic anti-imperialism, as well as contemporary upheavals in Russia, South Africa and Japan.

Through his polemical speeches and essays, Aurobindo furiously developed his political theology against a backdrop of assassination, robbery and bombings, weaving all of these strands into what Wolfers argues is the central symbolic archetype in his political theology: the ‘revolutionary Sannyasi’.

In Hindu philosophy, Sannyasis are religious ascetics – holy men who renounce society and worldly desires for an itinerant life of internal reflection and sacrifice. Throughout the late 18th century in famine-stricken Bengal, roving bands of Sannyasis – together with their Muslim counterparts, Fakirs – challenged the oppressive tax regime of the British, and repeatedly incited the starving peasants to rebel.

Aurobindo amplified and weaponised this already potent symbolic figure by recasting him as a channel for divine violence. By embodying Swaraj, the revolutionary Sannyasi could kill with sanctity. Violent revolution became spiritually transcendent, without murderous stain.

“Just as the traditional Sannyasi intensifies his inner divinity through ascetic practice or the voluntary embrace of suffering, Aurobindo venerates the element of violence and adversity in existence as a prelude to collective ‘self-overcoming’,” says Wolfers.

As Wolfers puts it, the revolutionary Sannyasi is the man of spirit and action, sanctified by sacrifice, whose volatile potency is ready to detonate like a bomb in a violent spectacle of Liebestod: the ‘love-death’ of German romanticism, the ecstatic destruction needed for rebirth. As Aurobindo himself states, “war is the law of creation”.

“This violent vanguardism is often seen as an infantile politics that limits broader participation in a political movement,” says Wolfers, “but even the non-violent Gandhi significantly borrowed from Aurobindo’s transgressive politics. This form of terrorism was crucial in implanting the radical ideals of Swaraj that later anti-imperialist politics were structured around.”

Aurobindo’s highly Anglicised, elite Cambridge education had left him estranged from his roots. On his return to India in 1893, he had to ‘re-learn his identity’ through classical Hindu texts, whereas his younger brother Barin, who had grown up closer to home, was more familiar with the living traditions of Bengal.

Together, Aurobindo, the prophetic visionary, and Barin, the untiring activist, organised the spread of a loose network of underground terrorist cells throughout the land and incited the increasingly politicised student communities of Bengal to submit themselves to the militant spirituality of the ‘revolutionary Sannyasi’.

“These young revolutionaries took their cues from Aurobindo’s discourses of Sannyasi renunciation: they left their families and society, living rigorously according to rituals and timetables, dressing in the traditional ochre robes of the Sannyasi. Some even made use of Tantric practices, carrying out blood rites and secret vows in cremation grounds to purify their life in contact with death,” says Wolfers. “Through these practices they cast off their allocated ‘middle classness’, breaking free from imposed British society.”

The revolutionaries targeted figures of British state authority and, in May 1908, Aurobindo was arrested in connection with the botched assassination attempt of a notorious magistrate. It was while in solitary confinement in Alipore jail that he experienced the ‘spiritual awakening’ that confirmed his mystic status.

Over 60 years after his death in 1950, Aurobindo’s legacy continues to live on, despite often being misappropriated for political gain.

“The figure of the ‘revolutionary Sannyasi’ has had an enormous afterlife: in its various guises and mutations, its influence is evident across the political spectrum from Gandhian mobilisation to Bengali Marxism and Hindu nationalism. Even today, it remains an important trope in Indian politics,” says Wolfers.

“From as early as the 1920s, Hindu nationalist organisations began to recast Aurobindo in an increasingly right-wing mould to assert Hindu dominance against the subcontinent’s Muslim and Christian minorities,” he says. “But hyper-masculine Hindu chauvinism, still a major force in Indian politics today, stands in sharp contrast with his original inclusive and ‘anarchic’ outlook.”